Hindu Nationalists Can’t Erase India’s Queer History

India has a long and rich queer history, but you’d never know it by listening to some modern-day Indians. The Indian Supreme Court recently rejected a proposal to legalise same-sex marriage, after a marathon hearing that lasted a full ten days. The case began when gay couple Supriya Chakraborty and Abhay Dang sought legal recognition for their marriage through a petition to the Indian Supreme Court in November of 2022. A further 18 same-sex couples followed their example, filing a petition in Delhi to have their unions recognised under the 1956 Hindu Marriage Act.

The petitioners, who were represented by some of India’s most eminent lawyers, including former Attorney General Mukul Rohatgi, argued that the failure to recognise their marriages deprives same-sex couples of their constitutionally guaranteed right to equality under the law, in accordance with a broad interpretation of Article 21 of the Indian Constitution: in which the state vows to protect the right to personal liberty.

The couples’ lawyers argued that when the Supreme Court recently decriminalised homosexuality, the Court conceded the principle that legal change can precede societal change — a principle embedded in the Constitution since it was established in 1949. In fact, India’s founding fathers were acutely aware of the need to use legal measures to reform some of India’s religious and societal norms (such as the idea of untouchability). B.R. Ambedkar, chair of the drafting committee and widely considered the architect of the Indian Constitution, wrote in 1936 that “constitutional morality is not a natural sentiment. It has to be cultivated.”

The state’s respondents, led by Solicitor General Tushar Mehta, argued that heterosexual marriage is foundational to the “existence and continuance of the state” and that the legal sanction of opposite-sex marriages would lead to “societal and cultural collapse.” This seems unlikely given that marriage equality is the law of the land in 34 countries around the world, the overwhelming majority of which are thriving, stable democracies. In India itself, the arguments against same-sex marriage are rooted in the same Victorian morality that inspired section 377 of the Indian Penal Code criminalizing homosexuality, a (now repealed) statute that dates from 1860, during the height of British rule. If we take a longer historical view, we will find that traditional Indian culture actually incorporated far more complex and nuanced attitudes towards same-sex love.

Westerners have long held orientalist and frankly silly misconceptions about Eastern sensuality. In History of Sexuality (1976), a work which has had tremendous influence on the modern LGBTQ+ movement, Michel Foucault argues that Western society creates a scientia sexualis — a science of sexuality — which divides sexual acts into different categories. He believes this system is underpinned by the assumption that there are fundamental moral truths that determine which sexual acts are permitted and which are taboo. The East, on the other hand, Foucault idealises in comparison. He argues that we practise the “ars erotica” and view sex primarily as a source of pleasure, unconstrained by a codified system of laws, and learned as an art form, from a master.

At first glance, this dichotomy can appear convincing — even alluring. The idea might flatter some of us Indians. Nevertheless, Foucault’s notions are simply not true. Instead, they reflect the hopes and dreams of a utopian looking for a better world in the “noble savage” outside of his own culture.

And yet, the great Indian erotic work, Vatsyayana’s Kamasutra (2nd–3rd century CE), features poetry, drama, and legend in the tradition of Indian performance arts in a manner that seems to prove Foucault right. However, major parts of it also read like a technical thesis, in which competing arguments are dispassionately presented and critically analysed. Clear distinctions are drawn between what is and isn’t sexually permissible. It advocates that homosexuality be less severely punished than theft, for example — but does imply that it should be punished.

But traditional Indian attitudes towards homosexuality are more complex than this might imply. Consider, for instance, the story of the birth of Bhagiratha from the 15th century Krittivasi Ramayan. Bhagiratha, the legendary Hindu king who is said to have brought the sacred river Ganges down from heaven to earth, was conceived during a sexual act between two women. However, Bhagiratha was born without bones, in accordance with the teachings of an ancient Sanskrit medical treatise called the Sushruta Samhita (6th century BCE), which states that any child who is the fruit of a lesbian coupling will be born with that defect. He only acquired a perfect body after he was blessed by the sage Ashtavakra. Hence, the Krittivasi Ramayan draws on myth and pseudoscience to craft a dramatic narrative about the birth of a crucial spiritual figure, conceived through a homosexual union.

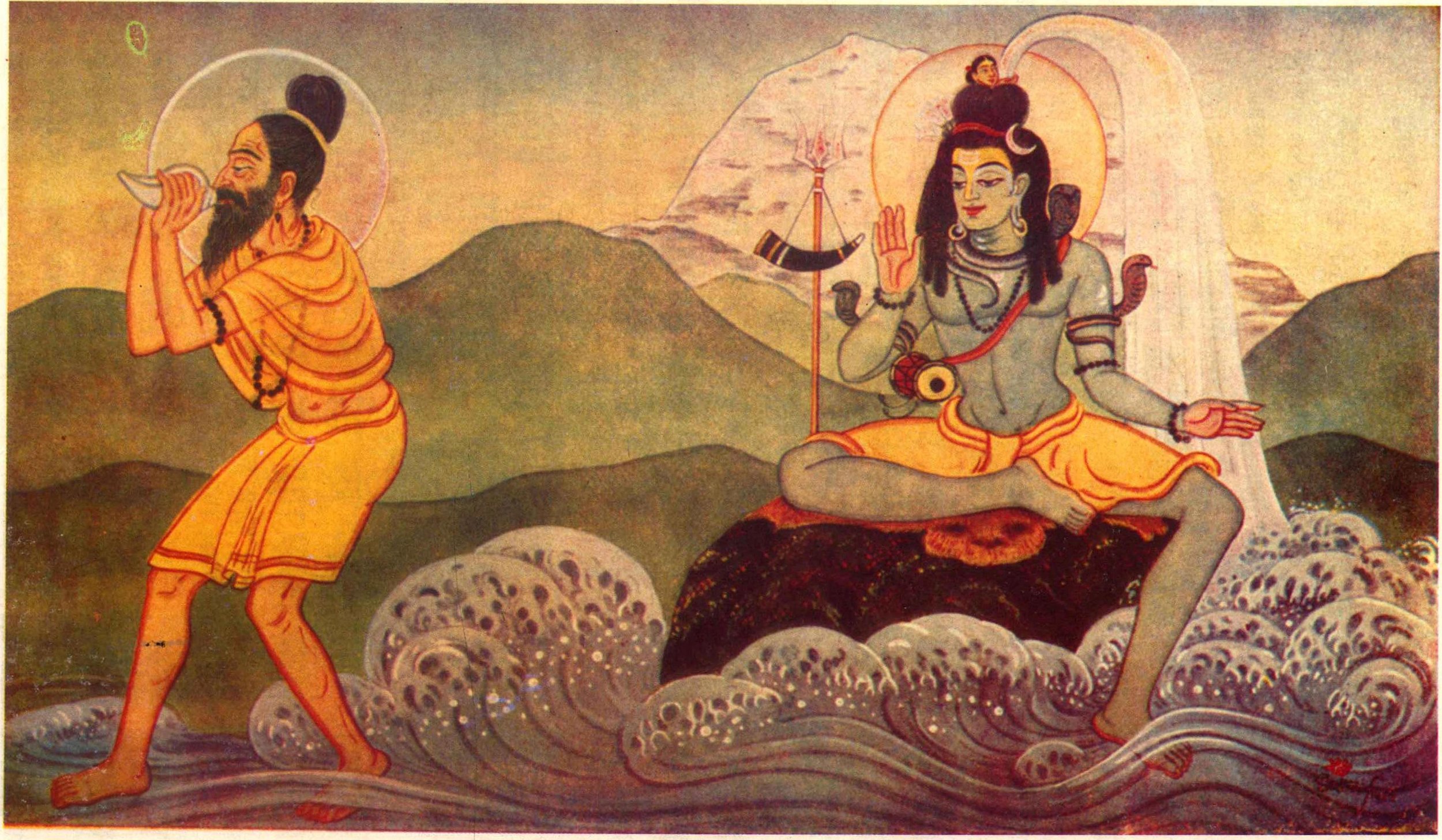

Representation of the Ganges.

In medieval India, paeans to amorous relationships between individuals of the same sex were common. The 16th century Sufi poet Shah Hussain, for example, is said to have fallen desperately in love with the Brahmin Madho Lal when they met during the Hindu festival of Holi and Lal threw the traditional celebratory coloured chalk over Hussain as they danced. Their families disapproved of the intimacy between the two men, but Hussain’s poet-biographer describes their relationship as not only permissible, but as a spiritual act, a crucial part of the quest to experience God:

When Hussain takes Madho’s lips in his own

he transmits his blessing in the most intimate way.

When Madho answers his lips with shy delicacy

he coaxes from each blessing many more blessings.

Hussain is training Madho from the depth of his soul

how to pass along the mystic path to truth.

Shah Hussain became popularly known as “Madho Lal” Hussain, taking his lover’s name like a wife. He is entombed next to Madho in Lahore, Pakistan.

This identification of the beloved with the divine is extremely common in both Hinduism and Sufism. In Hinduism, the god Krishna is most closely associated with the sensual experience of the divine, but the deity Rama has not been exempted from this kind of depiction. Contemporary Hindu nationalists treat Lord Rama as “Maryada Purushottam” (the perfect man), the defender of tradition and the status quo, and a paragon of purity, and therefore prefer sanitised portrayals of him. But their approach contrasts sharply with the depiction of Rama in the 17th century masterpiece Baidehisha Bilasa (“The Pleasures of Baidehi’s Husband”) by the poet Upendra Bhanja, who describes Rama’s relationship with his wife Sita in lovingly sensual detail. In one episode of the poem, Rama is travelling through a forest when he encounters a group of Brahmins, who are instantly smitten by the “beautiful blue-bodied man.” They exclaim:

The Lord should turn us into women

so that the one with the bow becomes our husband.

What is the point of being a brahmin?

How will we now become women?

Thinking this, excitement filled their bodies.

Shivering, they leaned on a tree.

As delusion filled their minds,

they started addressing their friends as women,

placed earthen pots on their chests,

and, happily, thought them to be their breasts.

Thinking their dreadlocks to be their braids,

they began adorning them with flowers.

Here, the celibate sages’ desire for Rama is described in distinctly queer terms. They want to turn into women in order to be able to marry him, and the thought of that transformation excites them to the point of autogynephilic pseudo-bisexuality (only when envisioning themselves as women do they experience attraction to a man) and psychosis (they actually start seeing each other as female).

British colonisers, many of whom came to India in the 19th century on a mission to “civilise” the country, brought with them their restrictive Victorian morality. Two Hindu organisations, the reformist Brahmo Samaj and the reactionary Arya Samaj, attempted to counter the efforts of Christian evangelists. But ironically, both associations adopted certain key elements of 19th century Anglican morality. Not only did they renounce Hinduism’s traditional polytheism and use of idols as superstitions, but they helped dramatically shift attitudes towards sexuality. In the 1890s, Upendra Bhanja was denounced for his obscenity. He had portrayed Rama as a “lowly beast driven by sexual desire,” the new Hindu establishment hissed, instead of the “ideal human being” that he was. Bhanja’s followers would prevent progress, his detractors alleged. In a 1938 book published by Oxford University Press, literary scholar Lajwanti Ramakrishna dismissed Shah Hussain’s aforementioned passion for Madho Lal as a mere rumour, arguing that he could not have been involved in such an “unnatural relationship.” Ignoring the testimony of Madho Lal Hussain’s earliest biographer, she argued that the two men lived together for purely practical reasons, because Madho Lal needed a place to stay after he was ostracised by contemporary Hindu society.

Homosexual and bisexual love was always tolerated and often accepted by wider society in pre-colonial India. It was certainly not always celebrated, nor did queer people have a strong sense of community (with the exception of the Hijras), but the lives of queer people were not uniformly defined by persecution. Some same-sex couples were even fêted, and their erotic love was seen as a legitimate means of approaching the knowledge of the ultimate beloved. The fact that millions still throng to the tombs of Madho Lal and Shah Hussain, now Sufi shrines, to celebrate their lives, poetry, and teachings, is a testament to the cultural acceptance of historical queer figures. It is ironic that one of the last vestiges of colonial Victorian sensibility to survive in India — long after it disappeared from its country of origin — is now being upheld by a government that constantly harps on about the necessity of decolonization.

Published Aug 30, 2023