The In-Between: The Poet and the Athlete

Since scrawling out my first poem at age seven, after my father died, I’ve always been drawn to art — but over time, as a young black man entering high school six feet tall, it was sports that increasingly seemed drawn to me.

Eventually, after all the hallway harassment from coaches begging me to join their teams, I couldn’t refuse it any longer. The opportunity was grand, and I knew it. But something unnerved me: no one knew I was still writing poetry.

With any great opportunity, it seems, comes a list of things you cannot do. When I finally did put on my high school uniform, I agreed to a perceived conformity I believed would bring me success in football. Just as there were things I could not eat and schedules I could not negotiate, I sensed that the rosy abstractions of poetry just didn’t square with the lunk and clank of football players. Add to that a new social politics, informed on the field and off, and a litany of other new dynamics, and I began to realize that as the sport swelled up in my life, the constraints only grew.

Poetry, writing, and art, on the other hand, had no limits — and this is what drew me in. Rhyme scheme, meter, stanzas — I could follow a strict structure or let an emotion rip it all apart; it was up to me. My poems could look completely different from one another. There was no reason to suffocate art with a uniform.

When I told people I was a football player, they acted as though I had told them everything they needed to know about me. Their only follow-up questions were about what team I played for and what my position was, even if they knew little or nothing about the sport. When I tell someone I am an artist on the other hand, the questions are endless: Who are your influences? What made you start creating? What type of art form is your favorite? I wanted to have both of these conversations — as the artist and as the football player. But it seemed like there was no place for art and athletics to coexist.

I got awards for writing and poetry in school but laughed them off whenever teammates heard about them. I got A's in English but felt exposed and naked when teachers praised my work. When I won a full scholarship to play football at Purdue University, I didn't even look into its creative writing programs because I assumed it wasn't an option for me. But who was it, exactly, who said I couldn’t do both?

Social attitudes in the United States maintain that an athlete’s only goal should be to be a better athlete. Fox News pundit Laura Ingraham said as much in 2018 when she told Lebron James (one of the greatest basketball players of all time) to “shut up and dribble” in response to political comments he made on the state of our nation. Though out of line, and arguably reeking of racism, Ingraham’s remark wasn't much of a shock to me — she was articulating a mentality that a lot of people, even including some athletes, share about the role of athletes in society. Colin Kaepernick and Muhammad Ali are two other well-known examples of individuals whose efforts to speak on matters beyond the world of sports have been met with social criticism and pushback.

As I grew unfulfilled by this restrictive attitude, I saw some of my peers break from the stereotype to embrace more of their passions. Wide receiver Odell Beckham Jr. started pursuing fashion, NBA player Kevin Love began speaking out about mental health, linebacker Spencer Paysinger created the hit television series All American (2018– ), and Lebron started his own media company with the slogan “More than an Athlete.” I thought, there must be more athletes like me with passions growing and burning inside, scared to embrace them.

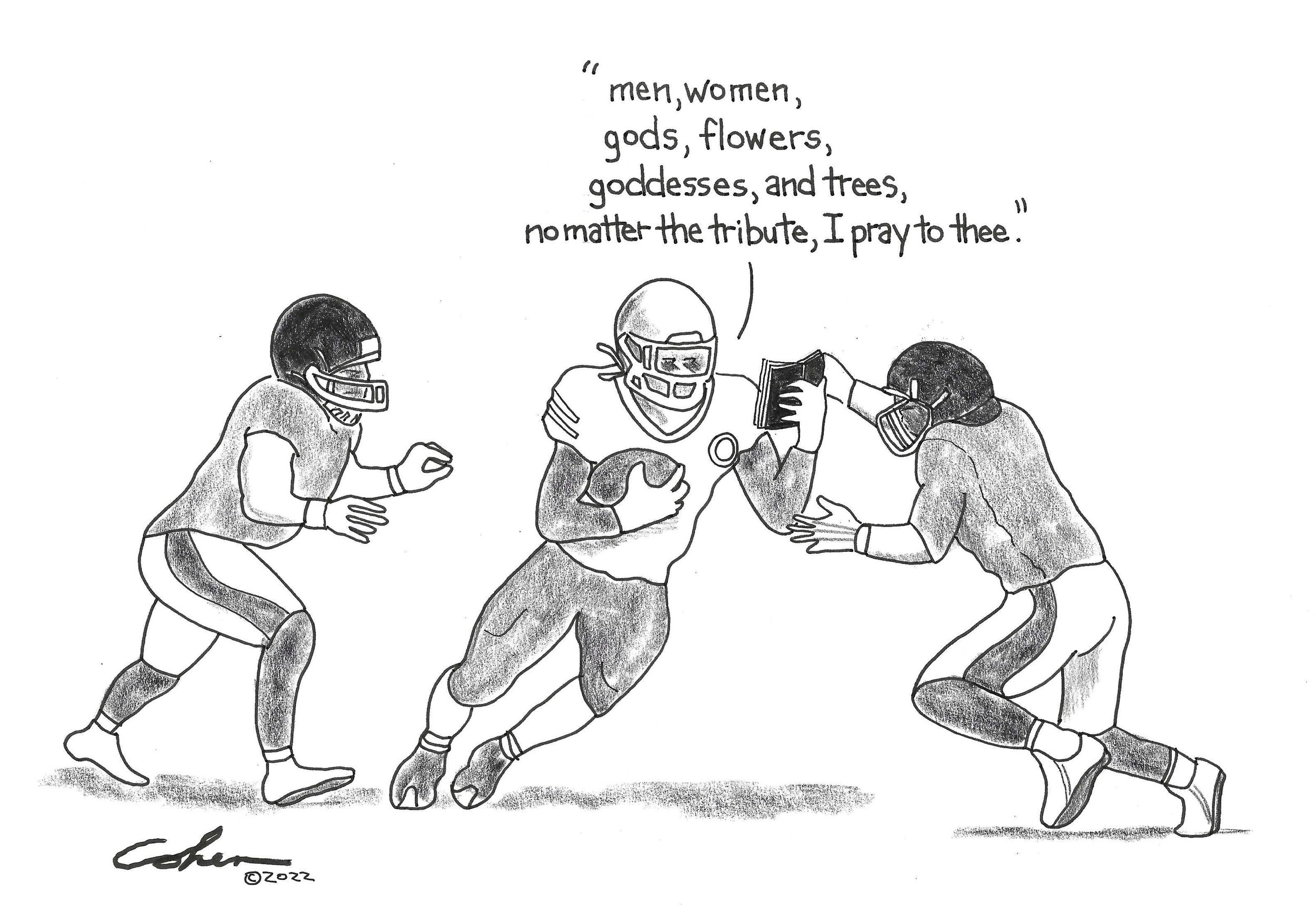

There is a meticulous control that comes with football — every step, every movement, every play. Technique must be executed with robot-like precision — you work tirelessly to bend your body, and your opponent, to your will. I tried to apply this same control to my life. Yet artistry and athletics had to coexist in some form, even if only inside me. So, I began to acknowledge the intersections that I inhabited and started to lift them up rather than hide them.

In doing so, I discovered that sports are a lot like art. Every movement is a stroke of the brush. The field was our canvas and my teammates and I were always eager to share with the world the improvised work we had dedicated our lives to creating.

Football was my saving grace. Because of football I was able to get an amazing education, meet exceptional people, and support my family. Why wouldn't I want to share that in the most eloquent and beautiful art form I was capable of? Even so, it would be a long time before I attempted to write a poem about football. The intrinsic expressivity crossed with such a macho trade still felt taboo.

When I finally did get past this feeling, I couldn’t stop: My poems explored the brotherhood I experienced with teammates, the father figures I gained in coaches, the humility of a hard-won victory, and resilience in a heart-shattering defeat. I found that sharing these poems with my friends, at poetry readings, and in my book brought an appreciation of the sport to a wider audience. And though not every poem was positive (many offered honest introspection of myself and the game), teammates who read my work confessed they shared many of the feelings and experiences I expressed through not just my poetry of football but my poetry of life.

I spent years caught between these two parts of myself: the poet and the athlete. I was constantly fighting to hide or suppress one side or the other, not realizing that the in-between of athletics and art was where I felt most at home, most myself, and where I could make my truest connections and achieve my biggest dreams. When I did wake up to this fact, I finally felt whole and seen by both the art world and the sports world. Some days I still can’t believe I get to live in between these two things I love so dearly and claim them both wholeheartedly. I am convinced it is up to all of us to embrace such in-between spaces within ourselves and in others. So nowadays I make sure to not only ask someone what they do for work, but also what they do to make themselves happy. Knowing both is enlightening because in the middle of these answers is always undeniably, unquestionably you.

Published Sep 30, 2020

Updated Jan 25, 2024

Published in Issue VIII: Art