Artist Feature: David Cicirelli

The latest edition of All Minus One, an illustrated iteration of Victorian philosopher John Stuart Mill’s famous essay, On Liberty (1859), provides an extremely appropriate point of discussion for this issue of Queer Majority, in which we examine the concept of clashing ideologies. I spoke to Dave Cicirelli about the process of illustrating this project and how it aligns with his career and philosophies past, present, and upcoming.

This project initially came about with the meeting of two men: Mill Scholar Dr. Richard Reeves, author of John Stuart Mill: Victorian Firebrand (2007), who is studying inequality at the Brookings Institution, and Dr. Jonathan Haidt, who is a professor of Ethical Leadership and a social psychologist studying morality at New York University. Haidt is also a chair of Heterodox Academy, a worldwide, non-partisan association of researchers and educators dedicated to the dissemination and celebration of open inquiry, viewpoint diversity, and constructive disagreement. The academy’s vision of the future is one in which teachers and students can successfully challenge ingrained habits, knee-jerk or emotive reactions, and prejudiced modes of thinking, replacing these with innovative problem-solving, a genuine receptiveness towards new or unfamiliar ideas, and a willingness to learn from others with opposing viewpoints. Beginning as a blog run by a handful of professors, it’s now grown to a community boasting more than five thousand members, spread throughout 57 countries and 49 out of the 50 United States of America.

With this in mind, it’s no wonder that Reeves and Haidt, who connected through Heterodox Academy, were drawn together to create a modernised and accessible version of the provocative philosophies espoused in Mill’s On Liberty. If you’re unfamiliar with Mill, you might be wondering what relevance a 19th-century thinker and political economist has to do with our current cultural landscape. For me, perhaps the most striking takeaway of All Minus One (accentuated by Dave Cicirelli’s gripping illustrations) was just how shockingly pertinent — and perhaps even necessary — Mill’s advocacy for freedom of opinion and open discussion remains.

On Liberty consists of four chapters, or parts. The first is an introduction, which discusses the struggle between authority and liberty (setting up the argument that the tyranny of government must be held in check by the liberty of the citizens) and criticising the liberal project of the Enlightenment, which, in democratic terms, he felt had failed to meet expectations. The second chapter, on which All Minus One solely focuses, explores what true liberty of thought and discussion must, in Mill’s opinion, involve. It argues (in short) that no opinion, however provocative or controversial, must ever be oppressed. The third chapter posits that conformity is dangerous and that individuality is, by definition, a key element of well-being since it’s only through individuality that humankind can enjoy the “higher pleasures” (of intellect, of feelings and imagination, and of moral sentiments). In the fourth and final chapter, Mill delineates a formula with which we can deduce what, if any, aspects of life can or should be decided upon by governments on behalf of the individual, and which the individual should be able to decide upon by themselves.

Dave is an interdisciplinary artist, illustrator, and creative director with a wealth of experience working with entertainment and consumer brands. Before starting this piece, I thought it might be difficult to summarise and do justice to the work of a creative whose portfolio spans many different styles and forms. However, during our interview, it quickly became clear that Dave’s work, no matter how diverse, demonstrates a recognisable and recurring theme or philosophy: that of, in his words, the fallibility of our own perception.

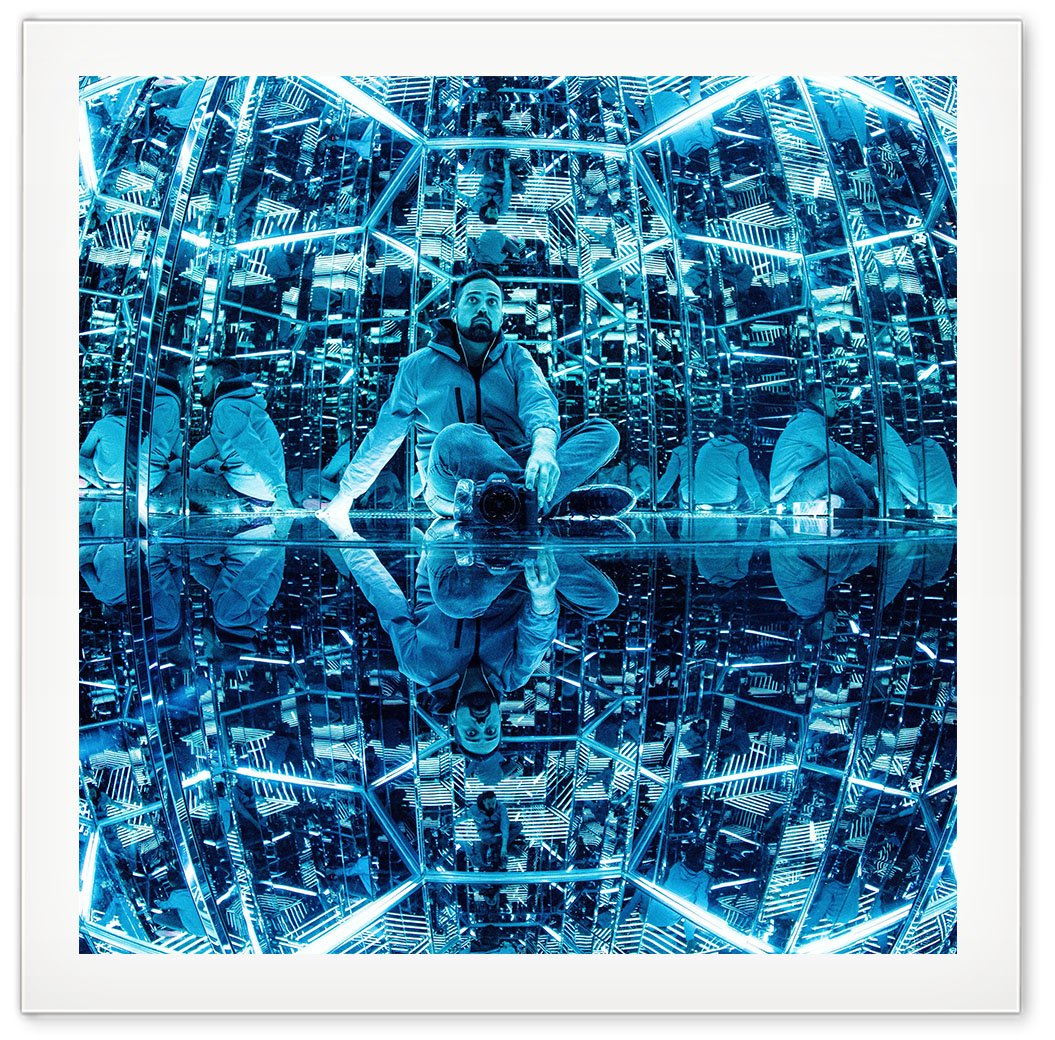

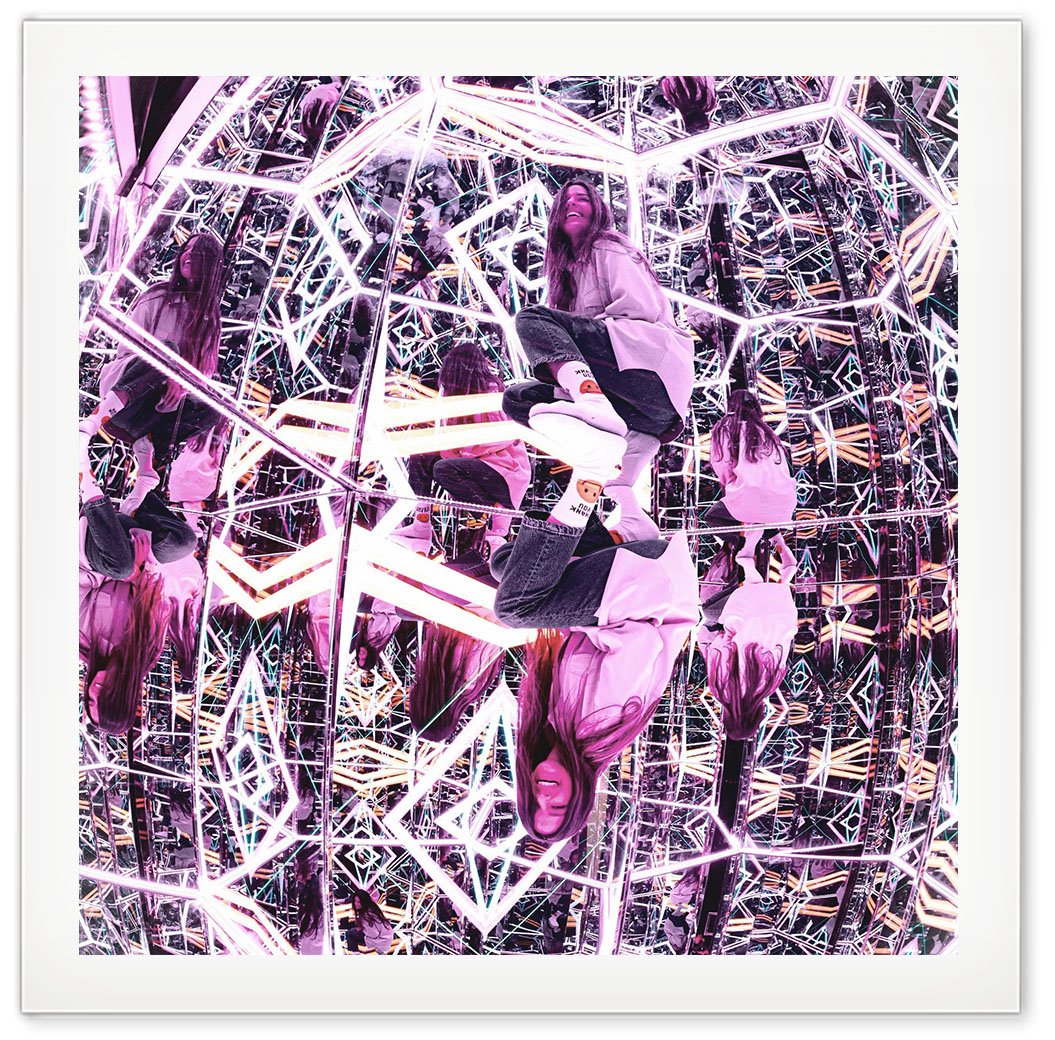

For example, his Vanity Project, an interactive Infinity Cube experience and experiment, was designed to reflect on its exterior a video feed of its interior, endlessly outwards in all directions. Participants within, posing for pictures or pulling faces, would not be able to see outwards, but audience members outside of the cube would see the participants’ image mirrored ad infinitum. This experience, simultaneously communicative and isolating in its nature, was intended as a send-up of the performative and curated digital world the majority of us inhabit. And even if we don’t, we are at least aware of its socio-political gravitational pull, considering our current climate in which the dominance of social media and the curation of our online selves have become the main vehicle through which information, from the inconsequential to the globally significant, is exchanged.

Similarly, Dave’s FakeBook, a social experiment in which his falsified online self created a year-long narrative, building connections based on this falsehood along the way, highlighted the ease with which one can misrepresent oneself in the digital world even before fake news and misinformation were as endemic as they are today. This elaborate, ahead-of-its-time concoction blended fact and fiction, exploring the idea of what relationships, reputation, and perhaps most importantly, the concept of truth, might mean to us in the 21st century.

It should come as no surprise, then, that Dave reached out to Richard and Jonathan upon learning about All Minus One and offered to illustrate it pro bono. He believed in the project, recognising that Mill’s evocative and metaphor-rich text would benefit from a tangible, throat-gripping visual representation of the ideas espoused within. Richard and Johnathan agreed.

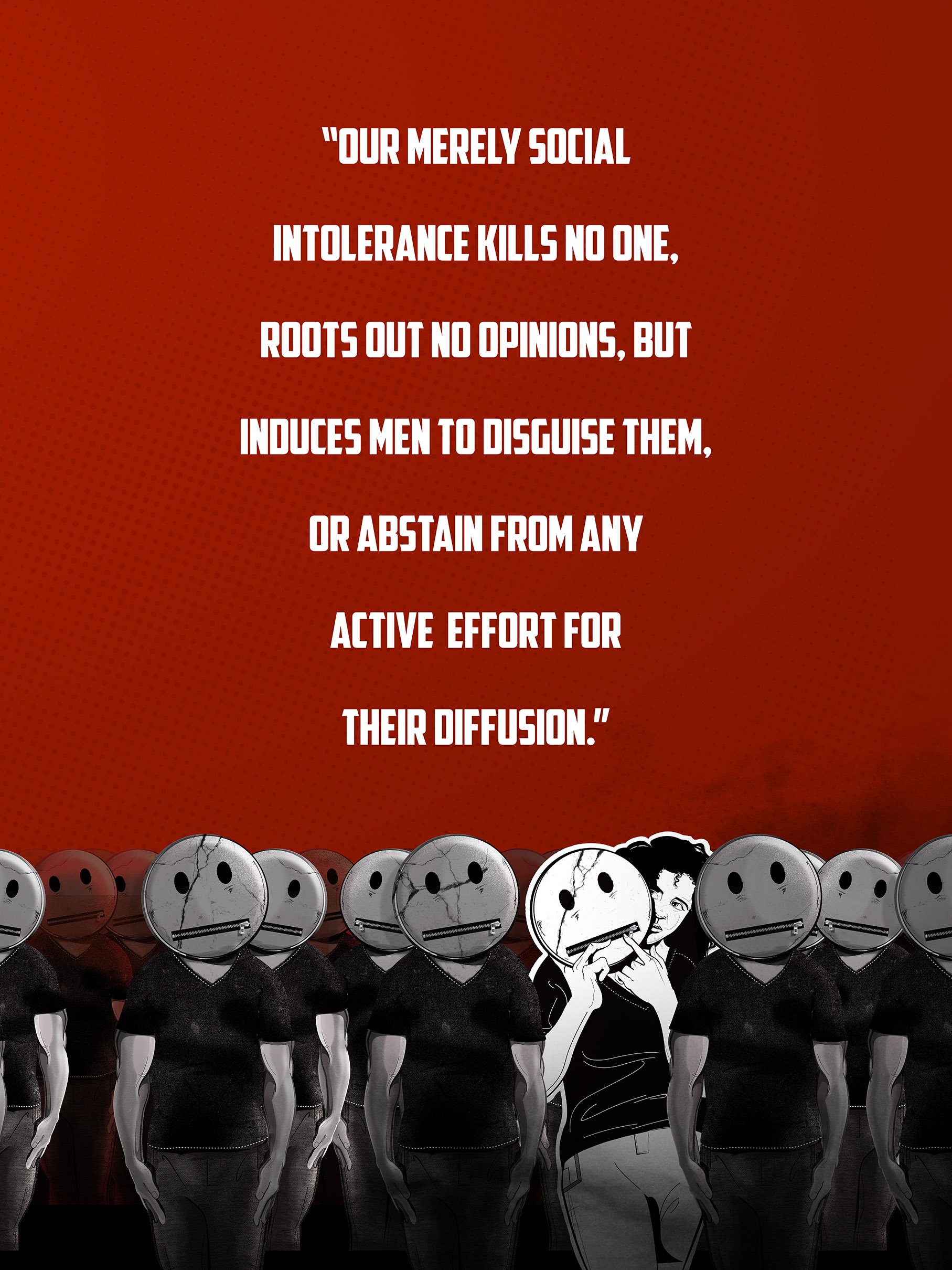

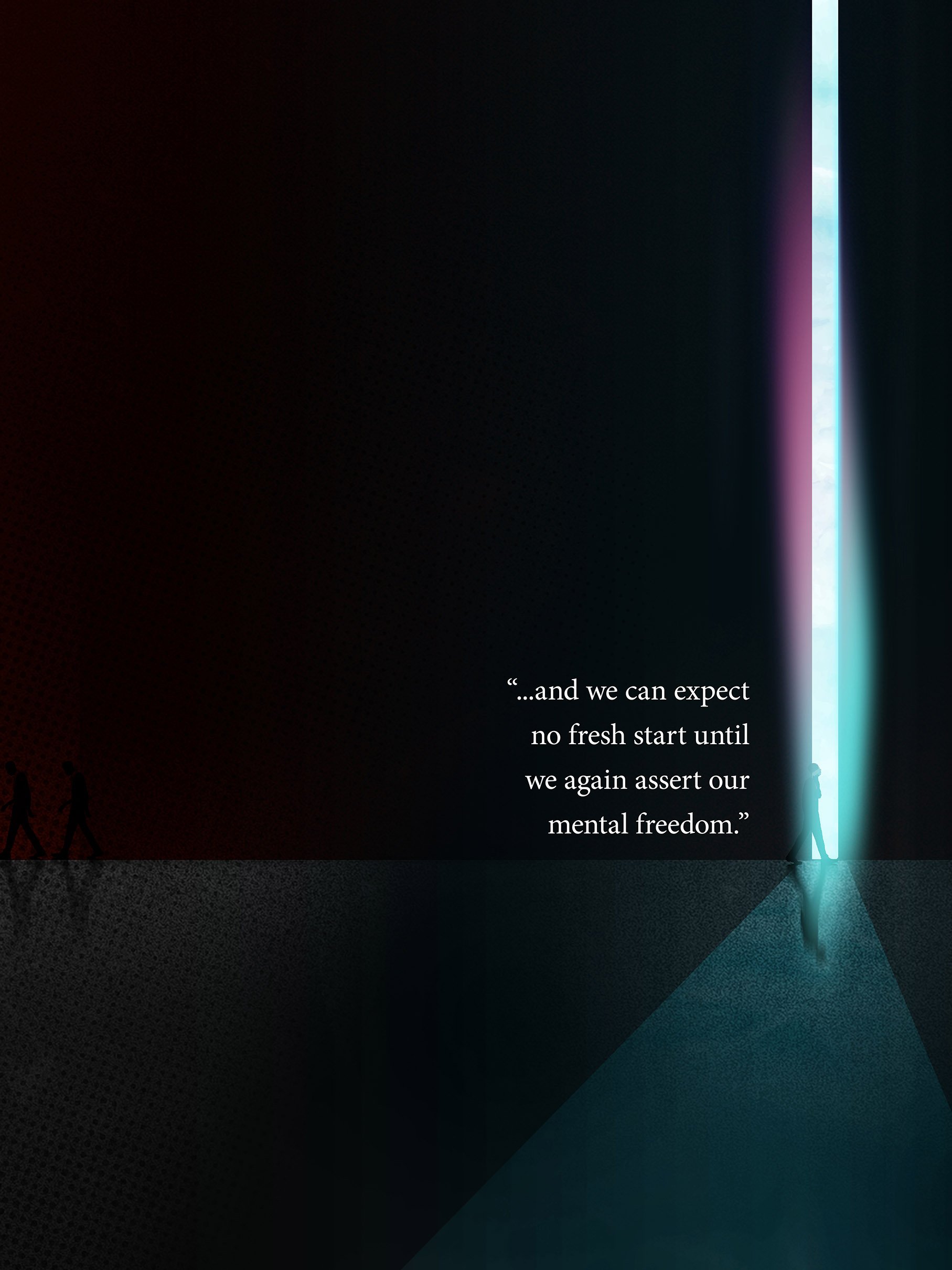

Dave’s approach is curiosity-driven, with theme and content influencing the medium, and not the other way around: “I like an idea, and I follow it.” Therefore, the parameters of the project — responding to a centuries-old text in an accessible way and distilling its key tenets and metaphors all the way down to a series of images — presented a unique challenge. Dave realised that the most succinct way of representing the central ideas of Mill’s text would be through the visual arc of an escape plan: one that moves towards vibrancy, optimism, hope, and enlightenment from a beginning mired in darkness, oppression, and obscurity.

The propaganda-inspired illustrations of the text’s beginning evoke oppressive and stifling militaristic regimes. This is only alleviated when, on page 19, we see a single figure breaking away from the conformity expressed and upheld in the illustrations thus far. They open a page-high door to an outside world beyond their current, limited reality, represented by a fluorescent beam of light in blue and purple tones, the rays spilling across and illuminating the floor in stark contrast to the heavy and claustrophobic blood-red and black of the piece thus far. The escape has begun. The impact of this page is accentuated by its layout: page seventeen ends with the sentence “we can expect no fresh start…” trailing off; the only words on page 18, alongside the figure opening the door to see the crack of light, are “until we again assert our mental freedom.”

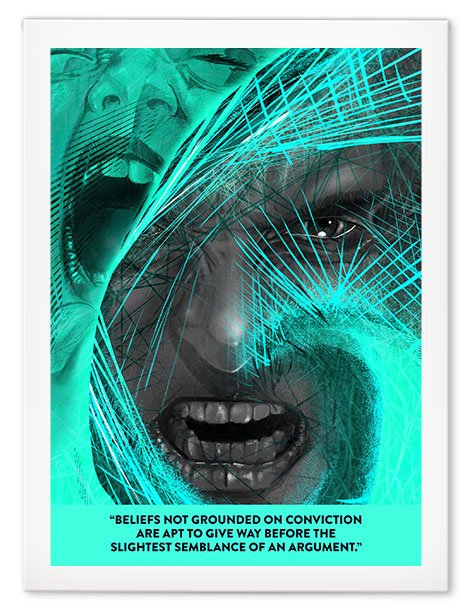

The single, non-conforming figure represents the argument from which the piece’s title derives: Mill argued that if everybody in the world — except one person — were to hold a single opinion, that lone dissenting voice would be just as valid and worthy of being heard as the billions of others it contradicts. There are three reasons for this. Firstly, that opinion, however strange or controversial it may seem at the time, may, in fact, be correct. Secondly, even if the one dissenting person is incorrect, those who disagree will hold their beliefs more rationally and securely as a result of being challenged. Thirdly, according to Mill, even opposing or seemingly contradictory viewpoints can contain an amount of truth and can, therefore, only benefit by being assimilated through comparison and intellectual agitation. This is a sentiment shared by Dave, who firmly believes that “opinion lands on a landscape, not a line.” He is disheartened by the divisive, emotion-driven, and often insular “us and them” attitudes and groups that political and global issues create and perpetuate, a phenomenon frequently exacerbated by online echo chambers and virtue-signalling. Often, he argues, people use these platforms not to express or discuss their opinions with a true openness towards debate and education, but to signal to the groups of which they’re already a part how firmly they hold their own beliefs. Dave tells me that it’s (sadly) no longer enough to be broadly against a thing; instead, we as a culture have fallen into the habit of feeling that we must advertise our own antipathy towards a person, concept, or legislation without being willing to hear anything to the contrary.

He calls this “a purity game, a righteousness that gives you a little sugar high” and adds that doing so is only creating a lie — after all, how sincere can our opinions be if we performatively share them for internet clout? More importantly, how strongly held can these convictions truly be if they will not withstand scrutiny, criticism, or even contact from what we perceive as the ‘other’?

“Most people are not happy with the way we’re having conversations,” he tells me, “but some are holding everyone else hostage.”

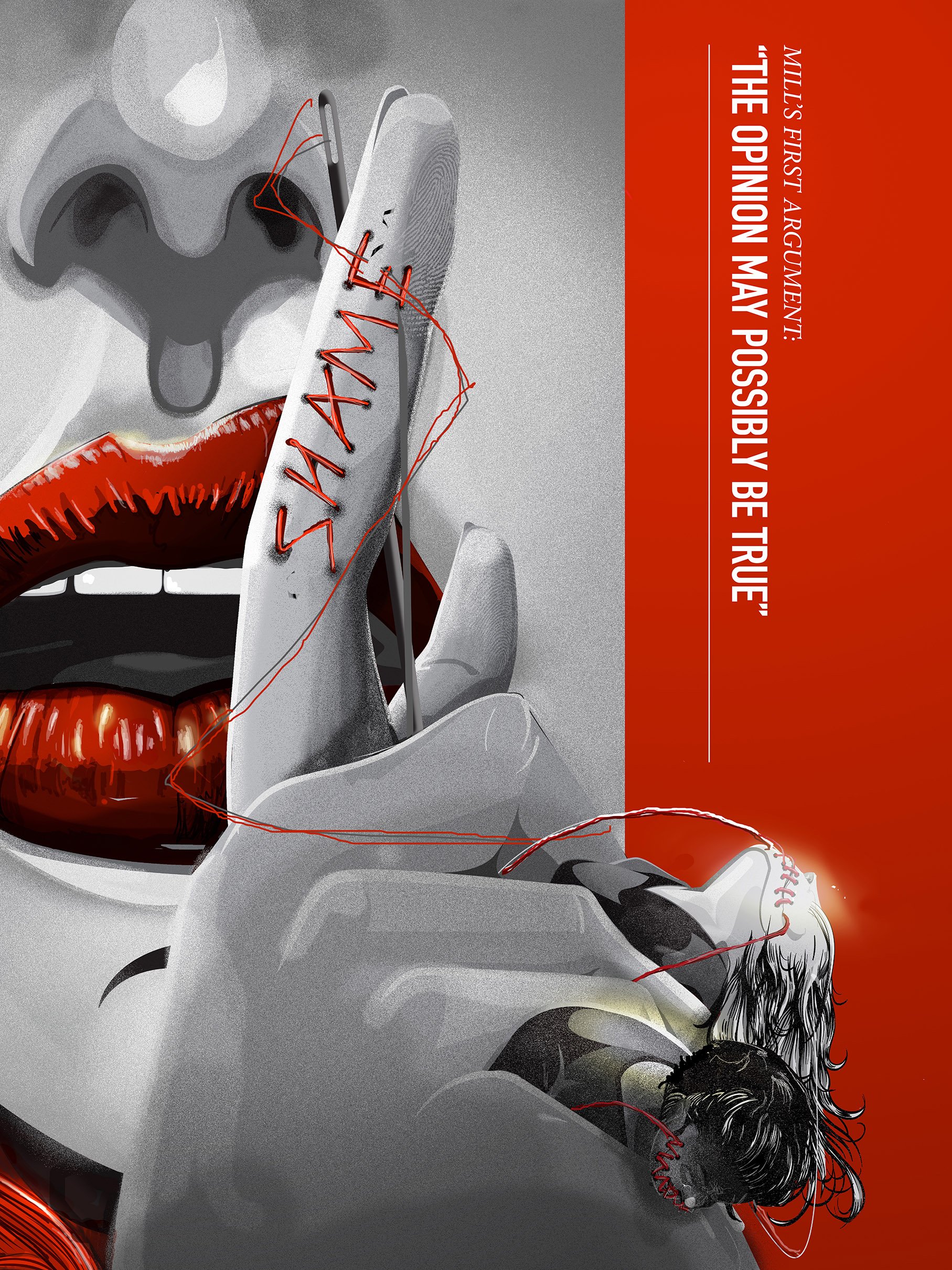

Mill argues that conflict argues for contact. Instead of clashing ideologies being lobbed at one another from afar, never touching or changing the other, Mill, the team at Heterodox Academy, and Dave believe that true growth can only come from a symbiotic exchange of ideas rather than a volley. Hence Dave’s image on pages five and six, of a mouth being stitched shut; the person doing the stitching is simultaneously shutting themselves off from being able to hear the voices of others. “What we can offer,” he tells me, “is an alternative to that pit in your stomach.”

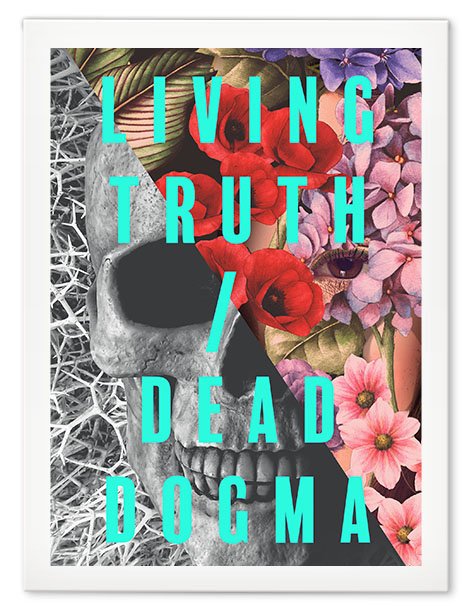

Dave’s interpretation of the text can be summarised in the difference between “dead dogma” and “living truth.” He evokes the metaphor of a walled and cultivated garden, which has become more isolated from the world around it: it is beautiful and familiar, but its inhabitants cannot withstand famine, droughts, or opposing armies at the gates, because of the comforts to which they’ve become accustomed. This, he writes, in an afterword to All Minus One, is his understanding of what Mill calls “dead dogma” “Living truth,” he argues, is found in the jungle from which the garden originated. “Bloom and rot share the same soil, and the scent of both lingers in the air. […] But we live in the wild too — and are accustomed to its dangers. We see these threats clearly. We confront them head-on.”

I, for one, agree. But that might just be the fallibility of my own perception.

For more about David, follow him on Instagram. For more about All Minus One, visit the Heterodox Academy.

Published Jan 5, 2022

Updated Apr 22, 2024

Published in Issue X: Clash of Ideologies