Je Suis Non-binary: Coming Out in Support of Free Speech

I t was a day when regular office talk suddenly felt absurd.

“Good morning, how are you doing?”

What could I say? I was an editor, and I was alive. And that statement wasn’t a given anymore.

In the days before, I had learned that an entire editorial team had been killed for doing what they thought was a good thing. When I name their magazine, you’ll recognize them immediately: Charlie Hebdo. 12 of its editors were shot to death during a board meeting, assassinated for publishing a cartoon that ridiculed the Prophet Muhammed. Now I was in an office surrounded by some of the most left-wing people you can imagine, all of us committed to ideas I had supported for years. Seeing them so unconcerned about free speech and the murder of fellow journalists, I felt rage and sadness — and on top of that, I felt so alone.

For me, this terrible news of another Islam-inspired terrorist attack forced me to face an unexpected personal turning point. I had made a stark realization: the world around me had changed so much that two major components of my life were now completely at odds. Because I experience my gender as somewhere in between man and woman, my job in journalism suddenly felt entirely incompatible with my identity. As a non-binary person, those who argued in favor of rights for “my kind” were on the far left — and those who argued for free speech were now, apparently, on the far right. There I was, dependent upon these warring and supposedly incompatible factions, and I had no idea how to solve that.

To understand why I found myself in such an impossible position, let me explain why the radical left had been so attractive to someone like me. That has to do with the concept of gender.

indebted to activist academia

“Are you a girl or a boy?”

It’s such a straightforward question, isn’t it? But for as long as I can remember, I didn’t know how to answer. My body seemed to provide people with visual cues about my supposed gender, but I didn’t feel that was relevant because my mind insisted I was something else. Growing up in the pre-Internet 1980s, I didn’t have any words for it. Then I saw a television program about a trans woman. Despite the sensationalism with which the topic was handled in that era, my brain lit up. I spent more than a decade wondering if I should transition as well, never knowing for sure what was right for me, yet always still feeling something was off. It was my struggle to deal with all this that led me to find a home in the radical left years ago.

It was the reason I chose gender studies as a major at University, where I encountered the philosophical theories that became the basis for my social justice activism. I learned how power and language worked to the disadvantage of the marginalized — something about which I cared deeply. I found it an exciting new way of looking at the world, though I found it unbearably light on the scientific proof.

One of those theories was queer theory, which says that your experience of gender (whether you feel like a man or a woman inside your brain) isn’t connected to your physical sex (your genitals). Even more enlightening, it states that gender isn’t an “either/or” condition, it isn’t “binary.” Recognizing that there were more options than simply being a man or a woman was a life-changing revelation for me, and it quieted my incessant gender questioning. I could finally move on, and I did that with a lifelong indebtedness to radical, left-wing, activist academia.

JOURNALISM

In the years after, the esoteric academic concepts I had studied found their way to the general public, though few people realized their origins. I kept seeing the same pattern of ideas around power and language that I now definitely recognized, and watching how it was playing out worried me. People on the left were gravitating toward the alarming conclusion that certain jokes should never be made, certain words should never be used, and certain ideas should never be questioned.

In the meantime, though my devotion to activist movements remained a constant, my life was moving away from academia. I had taken up a profession that also concerned itself with power and language — but always in pursuit of truth, backed up with data and based on more than one source. Ironically, my journalistic work was more rigorous than my academic work ever had been.

RIGHTS AND FREEDOMS

Working in journalism, not satire, I was not really aware of Charlie Hebdo until the attack, but when I heard about what happened, I felt a connection to them. I felt the work they did and the work I did, was very much the same. Robust journalism underpins a free society.

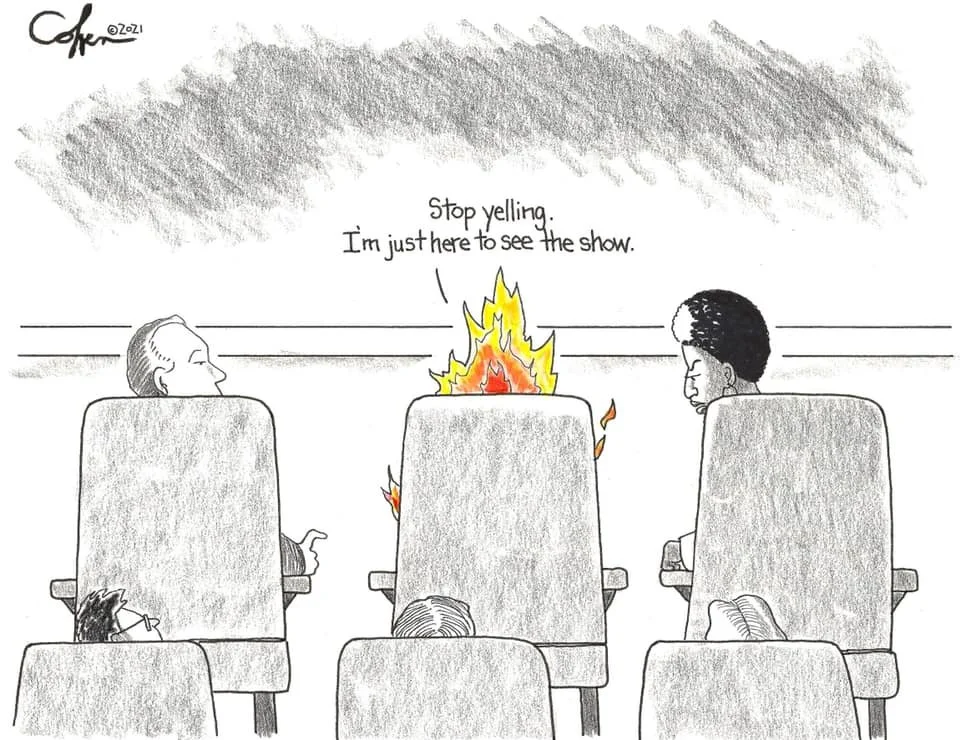

Authoritarian demagogues generally don’t like their policies to be questioned or ridiculed. Journalists are murdered all over the world for exposing abuses of power, and satirists who joke about the wrong people or ideologies disappear behind bars or appear on hit lists. Truth and questioning are the first things to go in a repressive society, even when they are delivered in a way that makes people laugh. An uncensored press and a culture of satire are great indicators of the level of rights and freedoms that people have within a society.

I had always believed these things were at the core of left-wing beliefs. They promote accountability for the powers that be, expose corruption and wrongdoing, and give a voice to the powerless. It turned out I was wrong.

THE CRITIQUE THAT NEVER CAME

That Wednesday in the winter of 2015, when those 12 editors died, it seemed everyone around me saw something entirely different than I did.

I scrolled through my social media feeds with a sinking heart. In post after post, my left-wing activist friends were using their ideas about power and language to the maximum, calling out anything that reeked of Islamophobia in the responses to the attack and stifling the debate around it into a black-and-white issue. It was completely well-intentioned, but completely off the mark. Only one satirist dared make a statement about it, a short, biting video that still feels relevant today. He was branded a racist — not that he cared, but he was one of the very few who took that risk.

In a sea of right-wing xenophobia, protests in the Muslim world, and social justice activists more concerned with Islamophobia than protecting the freedom of the press, I ached for solidly nuanced left-wing critiques. But there weren’t any.

It was clear to me that the free speech I wholeheartedly believed in — so much so that it had gotten me into several professional conflicts — now belonged to the opposite side of the political divide from the theories that had helped me finally understand my gender. And maybe it always had. At that point, I recognized that social justice is, at its very core, unequipped to support a free press. With that realization also came a fear: if I were to leave social justice behind and the theories that had meant so much to me, it would be a disaster for me as a non-binary person. The ways they had accommodated my identity had rendered the rest of the world unsafe and left me dependent upon them.

no alternative

Let me say something here that probably won’t make me many friends: I believe that it should be the left, not the right, which stands in support of showing the Muhammed cartoons. For the good of all of us.

Freedom of speech is fundamental to the success of a diverse society and essential for the freedom of everyone in it, including Muslim people. You cannot build a better world by employing the same repressive tactics used by the fundamentalist regimes you say you want to abolish. The right to offend is implied at the very core of our concept of individual freedom since many ideas, including religious ones, can be very offensive to others. The stifling of criticism and dissent does not create a peaceful society. People don’t become better people when you force them to use the right words. On the contrary, it drives otherwise reasonable people toward opposite, more extremist modes of discourse because they are given no alternative. And it goes without saying that it leaves those within marginalized communities powerless to dissent.

But unfortunately, the left has now seemingly instituted a hands-off policy when it comes to defending free press and satire. Nobody dares even to make a joke about anything remotely related to the issue anymore, and anybody who wears a “Je Suis Charlie” t-shirt is now supposedly a right-wing asshole.

There are real-life consequences to this. Problems exist that impact people who are in desperate need of support and who are instead being actively ignored in favor of policing the speech we use to talk about them — and it’s hurting people, including those like me. Women who work to end marital captivity or stop female genital mutilation are being silenced because of their supposed “Islamophobia”, and advocates are refusing to discuss anti-LGBT sentiments in non-Western countries unless it’s to place the blame solely on the shoulders of the West. And yet another desperate situation is unfolding now that will haunt us into the future. I shudder to think how the radical left can impact our stance toward the unlucky, liberal-minded people of Afghanistan, now trapped under Taliban rule after the US and its NATO allies have gone. My heart breaks when I think of Afghan women and LGBT people being abandoned by progressive movements afraid to come to their aid for fear of being labeled “colonialist.” Will we look back on this in a couple of decades and find ourselves on the right side of history with this kind of reasoning? I just can’t imagine that.

I think the left is making a massive mistake here. One I cannot support anymore.

Case in point: I spent the better part of two decades deeply embedded in radical left-wing activist circles. My gender identity is generally not understood, respected, or taken seriously anywhere else but there. I’m effectively giving up my home by dissenting. If you’re being abandoned by someone like me, with so much to lose by leaving, you’re doing something wrong.

back into the closet

Ironically, as I have been coming out more publicly as non-binary, I am also feeling the need to come out in support of free speech. It’s not been an easy thing to do. I worry about finding work as a non-binary yet “non-woke” person and fear I have to hide one of those things to get a job. I am racking my brain over what activism for non-binary rights would look like without the authoritarian trappings of the current movement. I worry about losing my community, too.

Apart from it all, I don’t think it’s safe to publicly say what I think about the Muhammed cartoons with my real name attached to it.

Work, activism, and community have been so intertwined in my life that it is hard to find solutions for each of them separately, but I’ve been trying to untangle them. I need a job and my gender identity shouldn’t matter for that. Who I am shouldn’t dictate my political or ideological views. Friends can be friends without needing to agree on everything. The personal doesn’t have to be political. But it’s easier said than done. I still don’t know how to reconcile the parts of queer theory that mean something to me with my love for science and the liberal ideas I am moving back toward. I still don’t know how it would work to exist as a non-binary person in a non-woke universe. Those few colleagues, friends, and fellow activists I have chatted with about this have literally stopped responding mid-conversation.

bigger than journalism

Is it worth it? When I think back to what sparked all this, I know what the alternative feels like: that deep, heart-wrenching loneliness I felt that day in the office years ago. At the end of it, as I was leaving, I stumbled into an awkward conversation with some colleagues. I asked them about the “Je Suis Charlie” demonstrations that were planned for that evening. Would they go? No, they said, they didn’t want to “play into the hands of right-wing people.” I felt my throat close up with disappointment. I hadn’t expected to be so alone with my grief. I decided to go anyway, even if I was alone. But I hid my face from any photographers because it was best not to be seen there. Not many things make you feel lonelier than the fear I had that evening. It felt like going back into the closet.

I don’t ever want to feel like that again, and I want others to know they aren’t alone either.

I have come to realize that this is bigger than journalism, bigger than being non-binary. That, maybe, if we ever want real, widespread support and acceptance for trans and non-binary identities — or if we want to achieve anything else for that matter — this is not how we are going to get there. I think if we want a viable alternative to social justice authoritarianism, a way towards real progress that helps everyone, non-binary and/or Muslim people included, we need to be able to have real discussions about the points of conflict that stand in our way. We need to be able to resist the temptation of retreating into tribalism, to resist our embrace of polarizing and extremist viewpoints simply because the alternative makes us uncomfortable. And we must stop being afraid of being scorned or shunned for standing up for the ideals in which we believe.

I, for one, am done with the fear of showing up authentically, if only because I am done with feeling lonely. I’m tired of silencing myself and letting the loudmouths dominate the conversation, of allowing them to pretend that their extremist positions represent the majority, or worse, that they have a superior take on politics and society which gives them the right to trample democracy. Words have power, let’s use them freely.

Published Jan 5, 2022

Updated Apr 19, 2024